There was no time to snooze, roll over or generally be slow to rise today. Even my unconscious brain registered this fact. When the alarm sounded early this morning, Tuesday, 18 March 2008, I proceeded to prepare for my day though a daze of sorts, but as quickly and quietly as possible. Showered, dressed and with my backpack ready, I grabbed my shoes from the pile of footwear at the door and moved outside. Sitting on the staircase in darkness, I put on my shoes while an unusual quietness fills the air, accompanied only by a cool breeze.

The walk from the apartment to the subway station was equally calm and quiet. There are few people on the streets of

Sagamigaoka

, some walking and others biking. An occasional vehicle passes and while others can be heard in the nearby distance. We move quickly and quietly, motivated by our strict timetable and the cool 50° F (10° C) temperatures, but are well ahead of schedule as we round the corner from the alley, approach the station and ascend the south entrance escalator.

It is 0434 JST when I take my first picture of the day—the deserted

Odakyu-Sagamihara Station

. Waiting on the westbound platform, I think about the mission we are about to embark upon. The first leg from here to

Machida Station

connecting to

Shin-Yokohama Station

is a familiar one, using the

Odakyu

and

JR East

systems. The second short leg will connect us to

Odawara Station

to begin leg three, a 494-mile (796-kilometre) journey west to the city of waters,

Hiroshima

,

Japan

.

The Hiroshima trip was something I thought about from the very beginning, during the initial decision-making and throughout the hastened planning stages thereafter. I felt it was something important to do, to visit the historic site of such horror and devastation. However, by the time airline tickets were purchased and I made the 27 January 2008

announcement, I had accepted Hiroshima as unattainable due to the raw travel time required ("a sixteen hour roundtrip commute").

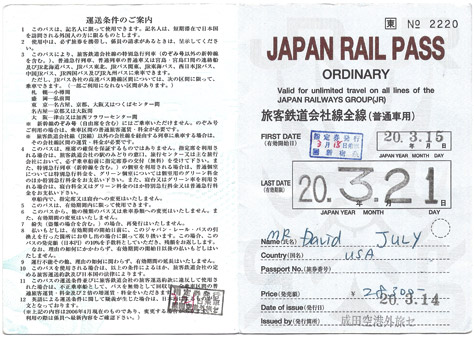

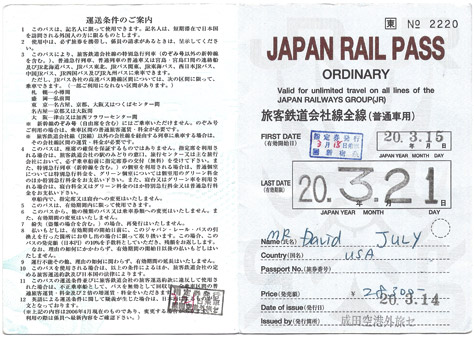

It did not take much further consideration, thinking about how I have no idea when I may return and how close I would be this time around, before I decided to do whatever was necessary to make it happen. The key to everything was the

Japan Rail Pass

by JR, available for tourists and purchasable outside of Japan only. We did not fully appreciate it at the time we acquired them, but the Japan Rail Pass was one of the best investments we could have made.

At ¥28,300 JPY (~$283 USD) each, the Japan Rail Pass granted us unlimited use of just about every JR train and bus service for seven days, with the notable exception of the

Nozomi  Shinkansen

Shinkansen

. While originally selected as the most cost-effective and speedy method of visiting Hiroshima in one day, the free use of the JR system proved invaluable during the entire course of the vacation. While using other train systems that did require additional payment was necessary on a daily basis, we were in many cases able to find alternate JR routes, furthering the value of the pass.

Before I knew it, I was aboard the 0615 JST

Tokaido Shinkansen

Hikari

Hikari  393

393 bound for Hiroshima. From seat

13-A aboard

Car 6, I watched the sunrise over the Japanese countryside and got my first glimpse at living outside the megalopolis. We are on board an

N700 Series Shinkansen, only added to the Hikari service days before our arrival in Japan. While still slower than the Nozomi, the new Hikari service is a significant improvement over other options, stopping briefly at only nine of twenty-five stations between Odawara and Hiroshima. Moving at speeds up to 168 MPH (270 KPH), the four-hour trip seemed to pass quickly as I gazed out the window and enjoyed the quiet, smooth and extremely comfortable ride.

Our arrival was scheduled for 1001 JST and as is custom, we actually arrived a few minutes

early. Navigating

Hiroshima Station

, we found ourselves at an information desk where the staff recommended transit via the

Hiroden

streetcar system,

Main Line

,

Route 6 to

Station M10

. Moving toward the streetcars, we find no customary fare machines and watch as scores of people get on without paying. The Route 6 streetcar departing at any moment, I decided we were smart enough to wing it and hopped aboard.

The older-looking streetcar is fairly crowded as it moves along the busy and modern city streets of downtown Hiroshima. Using the handle overhead to keep my balance standing, I try to inch gradually closer to the front of the car to try to figure out how exactly we pay the fare. After a few stops, I am finally able to see people paying at a device next to the driver similar to those found on city busses. I knew from the information booth that our ride would cost ¥150 but we had only larger bills and needed change. Despite our every effort to be quick as not to delay the passengers, it took us a minute to understand how the machine makes change. Quickly detecting our ignorance, the driver assisted by inserting the money into the correct slot, collecting the fare and handing back the change.

Mom maintains he flashed us a look as to say "stupid tourist." If true, this was a rare example in a country filled with extremely polite and helpful people. After exiting the streetcar, we made our way from the small platform in the middle of the street to the

Atomic Bomb Dome (Genbaku Dome)

.

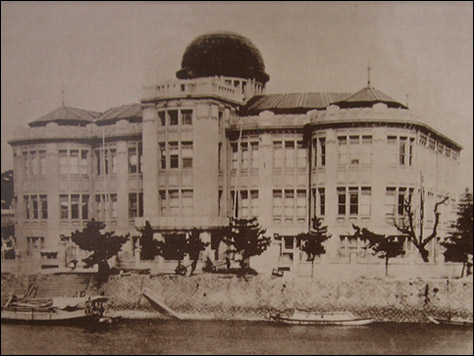

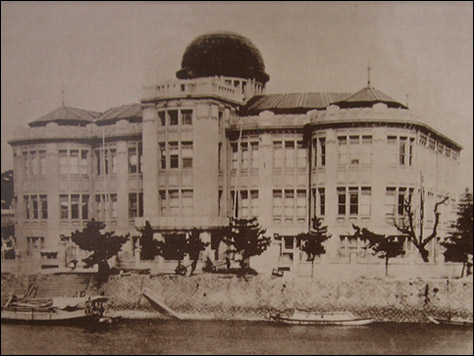

Also known as the

Hiroshima Peace Memorial and commonly called the

A-Bomb Dome, the 1915 structure was one of the few not completely destroyed by the bomb. Originally the

Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall

, the building was renamed to the

Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall

in 1921. During this time, the structure was used to display and sell prefectural products, house market research and small business consultation offices and serve as venue for art exhibitions, fairs and various cultural events. Later becoming the

Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall

in 1933, the building would soon serve new purposes as promotional activities dwindled during the war. By April 1944, the building was home to the

Interior Ministry Chugoku-Shikoku Public Works Office

, the

Hiroshima District Lumber Control Corporation

and other government offices.

After the detonation of the

Little Boy

uranium bomb at 0815 JST, Monday, 06 August 1945, approximately 1,969 feet (600 metres) above and 525 feet (160 metres) to the southeast of the Dome, the building's occupants were instantly killed, the structure itself gutted by fire. Due to the direction of the blast and the physics at work, the walls and still-recognizable dome remained standing. In 1960, sixteen-year-old

Hiroko Kajiyama

died of leukemia, exposed to the bomb 0.75 miles (1,250 metres) from the hypocentre at age one. After reading an excerpt from her diary which basically said, "I think only that ravaged Industrial Promotion Hall (A-bomb Dome) will be there to tell the world how fearsome atomic bombs are," the children of the

Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, compelled to act on her behalf, started what became the Dome preservation movement. Their 1960 flyer containing Hiroko's quote helped the growing campaign and by 1966, the

Hiroshima City Council passed a resolution declaring the A-Bomb Dome would be "preserved in perpetuity." Thirty years later in 1996, the Dome was designated a

World Heritage Site

by the

UNESCO

as a "stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind" and "the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons."

Walking south toward the Dome, the lush green and metropolitan surroundings are a strange contrast to the gutted structure, looking still as it did that Monday morning not so long ago. I silently walk around, photographing and taking it all in, as they say. Moving from the Dome and surrounding monuments, I come to the

Mobilized Students Memorial Tower

, completed 15 July 1967 to recognize the children forced by law to perform labor service who subsequently died in the bombing. Of the 8,400 middle school aged and older students in Hiroshima, 6,300 or 75% of them perished.

Crossing the

Motoyasu Bridge

, we move into the main portion of

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

, encompassing 1.3 million square feet (122,100 square metres) of green parkland between the

Honkawa

and

Motoyasu  Rivers

Rivers. After walking north to take pictures of the Dome from across the Motoyasu River, I moved south through the large collection of monuments and other remembrances starting with the

Peace Clock Tower

. Completed 28 October 1967, this unusually designed clock tower of 66 feet (20 metres) chimes daily at 0815 as a "prayer for perpetual peace and appeal to the peoples of the world that the wish be answered promptly."

Next, I came to the

Peace Bell

, dedicated 20 September 1964 "as a symbol of Hiroshima aspiration: let all nuclear arms and wars be gone and the nations live in true peace." Since all with the desire for peace are invited to chime the bell, I walked up, grabbed the hanging mallet and tolled. The muted but resonant sound was not very loud, but I was striking softly as instructed. In fact, my first attempt failed when the mallet had insufficient momentum to make contact with the bell's surface. I pulled back a little further on the second try and succeeded. While researching this article, I had occasion to watch many videos of Hiroshima visitors, all of whom had to try twice to ring the bell. I wonder if the mallet's rope is wound tight on purpose to help prevent excessive wear.

Continuing through the park, I next arrived at the

Children's Peace Monument

. Unveiled on 05 May 1958 as a monument to the children, the memorial itself was inspired by the death of twelve-year-old

Sadako Sasaki

whose classmates began the call for such a monument. Paper cranes are continuously made and donated for display in the cases surrounding the three-legged monument pedestal, atop which stands the bronze figure of a girl holding a crane.

Backtracking a bit to catch the rest of the monuments on the northern side of the park, I reach the

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

. After taking a few pictures, I find the sign and learn that this monument was the original site where deceased victims were gathered and cremated. The

Hiroshima Memorial Service Association built the original cinerarium here in January 1946, which was later replaced by the City of Hiroshima in July 1955 by the current cinerarium and monument.

The next remembrance I came upon is the

Figure of the Merciful Goddess of Peace

(06 August 1956), recognizing the former

Nakajima

neighborhood, the present-day site of the Peace Park and preserved only in memory and detailed maps reconstructed by survivors. After the

Korean Victims Memorial

(10 April 1970), I moved toward the open, central part of the park and approached the

Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims

(Memorial Monument for Hiroshima, City of Peace)

.

Built on 06 August 1952 with the desire to reconstruct Hiroshima as an enduring city of peace, the Cenotaph is constructed such that through it to the north can be seen the

Flame of Peace

(01 August 1964) and Atomic Bomb Dome. The stone chest inside contains the official registry of all those who died as a result of the bombing, a figure of 221,893 as of 06 August 2001.

While observing the memorial, a man dressed in an all-white robe and

Geta

wooden sandals took position immediately in front of the Cenotaph and did what looked like

Shinto

prayers due to their similarity to the rituals I observed a few days earlier at the

Zojo-ji

and

Meiji

Shrines. After a moment, he assumed a military-style salute position and stood tall for a few minutes before gathering his belongings and leaving. We meanwhile explored the rest of the grounds nearby including the

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

(August 1955) which we would later enter, the

Statue of Mother and Child in the Storm

(05 September 1960) and the recently added

Gates of Peace

(30 July 2005).

Before heading back and visiting the museum, we frankly needed a break from the memorial and decided to see more of modern Hiroshima. Walking through the nearby neighborhoods, I found Hiroshima indistinguishable from any other Japanese city, crowded and bustling with life. No exception was the

Hondori shopping arcade

, which provided the opportunity to try some non-Japanese Japanese food.

I had seen the signs for

Lotteria

earlier on

Takeshita Street

and elsewhere, but it was not until I saw the huge banner of a cheesy burger at the Hondori location did I understand what they sold. A Japanese burger, now how could I resist? I ordered the

Cheese Straight Burger

Set with

French Fried Potato

and a fountain drink. It was a tasty burger, too, similar but somehow different from a typical American fast food burger. And the fries, much like those I sampled the day before are distinctly different. I am not sure if it is the oil they are fried in or some other factor, but I really came to enjoy the crispier, slightly thicker-shelled and definitely less greasy version.

After lunch and some more walking around, it was time to return to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and tour the inside. The museum is comprehensive and contains many exhibits and artifacts, including a wristwatch stopped at 0815 by the force of the blast, a child's tricycle and metal helmet and a section of warped

Aioi Bridge

girder. While obviously discussing a serious and somber event, the material was presented in an informative and unbiased way I felt represented all sides and kept to the facts.

Some two hours later, we exited the museum and made our way to the

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

(2002), containing the

Hall of Remembrance

and resources like the victim name and photograph database and a vast library of memoirs and stories from the time and reflections thereafter.

It was now after 1700 JST, so we made a final pass through the park and stopped at the Aioi Bridge. I earlier learned in the museum that this unique T-shaped bridge was the designated target of the atomic bomb, though it missed by 984 feet (300 metres) and exploded over

Shima Hospital

instead. This bridge, replacing the repaired original in 1983, stands as a kind of crow's nest from which you can look out in all directions and see the results of the past, the monuments to the lost and the progress forward already made in rebuilding Hiroshima into a vibrant, pleasant city.

We walk to the same Hiroden streetcar stop we arrived at seven hours ago and get on the next Hiroshima Station-bound car that comes by, this time with a full understanding of how this unique transportation system works and exact change in hand. Waiting at

Track 14 for the Tokaido Shinkansen

Hikari 478 Rail Star to

Shin-Osaka Station

, the first leg in our long journey back to the apartment, we have been up for over fifteen hours. Although exhausted from the days of walking, I am surprised not to be as tired as expected.

As the

700 Series Shinkansen left the station promptly at 1851 JST, I was still filled with energy and exhilaration over all we managed to accomplish with the day. I took some mostly blurry night pictures out the train window and talked with Mom about the day and the trip so far. By now, we were feeling more comfortable than ever in our surroundings, with how to conduct business transactions and navigate the city. But the day still had one last adventure for us, one that would test if our comfort was justified.

The especially helpful JR ticket clerk who booked our reserved Shinkansen tickets days earlier understood our requirements to leave and return on the same day. What this meant for us was catching the first and last trains of the day. The getting there portion of this worked flawlessly with time to spare, but included no train changes. The return trip, however, included one such change—giving us only six minutes to make our connection aboard the

Hikari 434. We understood both trains would be near each other, but took no chances with the margin of error and were very prepared to depart the train when it pulled into Shin-Osaka Station.

We made the connection without issue and the rest of our trip back was uneventful, except for my sleepy mistaken impression we should exit the Odakyu train one station too early. We were close to home, but I was still very relieved to discover there was

one last train that would take us from here to Odakyu-Sagamihara. Twenty-one hours and 210 pictures after starting this day, we were once again walking the darkened, mostly deserted streets of Sagamigaoka eagerly heading toward bed.

Steven

and

Emma

were anxious to hear about the day, but after a few quick highlights, I was on the floor mat drifting off to sleep, thinking about the hours past and days yet to come.

Mount Sutro  presents

The Japan Trip Series

presents

The Japan Trip Series

[ Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six ]

Photograph Gallery

[ Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six ]

Photograph Gallery

Photo Credit: David July

Photo Credit: Carol Nichelson

From 13 to 21 March 2008, I vacationed in Tokyo

From 13 to 21 March 2008, I vacationed in Tokyo  , Japan

, Japan  to visit my friend Steven

to visit my friend Steven  and tour the area. Each day of this adventure is documented along with photographs and select Japanese translations. Select a day below to get started and then enjoy the photographs in the Gallery.

and tour the area. Each day of this adventure is documented along with photographs and select Japanese translations. Select a day below to get started and then enjoy the photographs in the Gallery.

presents The Japan Trip Series

[ Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six ] Photograph Gallery

There was no time to snooze, roll over or generally be slow to rise today. Even my unconscious brain registered this fact. When the alarm sounded early this morning, Tuesday, 18 March 2008, I proceeded to prepare for my day though a daze of sorts, but as quickly and quietly as possible. Showered, dressed and with my backpack ready, I grabbed my shoes from the pile of footwear at the door and moved outside. Sitting on the staircase in darkness, I put on my shoes while an unusual quietness fills the air, accompanied only by a cool breeze.

The walk from the apartment to the subway station was equally calm and quiet. There are few people on the streets of Sagamigaoka

There was no time to snooze, roll over or generally be slow to rise today. Even my unconscious brain registered this fact. When the alarm sounded early this morning, Tuesday, 18 March 2008, I proceeded to prepare for my day though a daze of sorts, but as quickly and quietly as possible. Showered, dressed and with my backpack ready, I grabbed my shoes from the pile of footwear at the door and moved outside. Sitting on the staircase in darkness, I put on my shoes while an unusual quietness fills the air, accompanied only by a cool breeze.

The walk from the apartment to the subway station was equally calm and quiet. There are few people on the streets of Sagamigaoka  , some walking and others biking. An occasional vehicle passes and while others can be heard in the nearby distance. We move quickly and quietly, motivated by our strict timetable and the cool 50° F (10° C) temperatures, but are well ahead of schedule as we round the corner from the alley, approach the station and ascend the south entrance escalator.

, some walking and others biking. An occasional vehicle passes and while others can be heard in the nearby distance. We move quickly and quietly, motivated by our strict timetable and the cool 50° F (10° C) temperatures, but are well ahead of schedule as we round the corner from the alley, approach the station and ascend the south entrance escalator.

It is 0434 JST when I take my first picture of the day—the deserted

It is 0434 JST when I take my first picture of the day—the deserted  . Waiting on the westbound platform, I think about the mission we are about to embark upon. The first leg from here to

. Waiting on the westbound platform, I think about the mission we are about to embark upon. The first leg from here to  connecting to

connecting to  is a familiar one, using the

is a familiar one, using the  and

and  systems. The second short leg will connect us to

systems. The second short leg will connect us to  to begin leg three, a 494-mile (796-kilometre) journey west to the city of waters,

to begin leg three, a 494-mile (796-kilometre) journey west to the city of waters,  , Japan

, Japan  by JR, available for tourists and purchasable outside of Japan only. We did not fully appreciate it at the time we acquired them, but the Japan Rail Pass was one of the best investments we could have made.

by JR, available for tourists and purchasable outside of Japan only. We did not fully appreciate it at the time we acquired them, but the Japan Rail Pass was one of the best investments we could have made.

At ¥28,300 JPY (~$283 USD) each, the Japan Rail Pass granted us unlimited use of just about every JR train and bus service for seven days, with the notable exception of the

At ¥28,300 JPY (~$283 USD) each, the Japan Rail Pass granted us unlimited use of just about every JR train and bus service for seven days, with the notable exception of the

. While originally selected as the most cost-effective and speedy method of visiting Hiroshima in one day, the free use of the JR system proved invaluable during the entire course of the vacation. While using other train systems that did require additional payment was necessary on a daily basis, we were in many cases able to find alternate JR routes, furthering the value of the pass.

. While originally selected as the most cost-effective and speedy method of visiting Hiroshima in one day, the free use of the JR system proved invaluable during the entire course of the vacation. While using other train systems that did require additional payment was necessary on a daily basis, we were in many cases able to find alternate JR routes, furthering the value of the pass.

Before I knew it, I was aboard the 0615 JST

Before I knew it, I was aboard the 0615 JST

393 bound for Hiroshima. From seat 13-A aboard Car 6, I watched the sunrise over the Japanese countryside and got my first glimpse at living outside the megalopolis. We are on board an

393 bound for Hiroshima. From seat 13-A aboard Car 6, I watched the sunrise over the Japanese countryside and got my first glimpse at living outside the megalopolis. We are on board an  Our arrival was scheduled for 1001 JST and as is custom, we actually arrived a few minutes early. Navigating

Our arrival was scheduled for 1001 JST and as is custom, we actually arrived a few minutes early. Navigating  , we found ourselves at an information desk where the staff recommended transit via the

, we found ourselves at an information desk where the staff recommended transit via the  streetcar system,

streetcar system,  ,

,  . Moving toward the streetcars, we find no customary fare machines and watch as scores of people get on without paying. The Route 6 streetcar departing at any moment, I decided we were smart enough to wing it and hopped aboard.

The older-looking streetcar is fairly crowded as it moves along the busy and modern city streets of downtown Hiroshima. Using the handle overhead to keep my balance standing, I try to inch gradually closer to the front of the car to try to figure out how exactly we pay the fare. After a few stops, I am finally able to see people paying at a device next to the driver similar to those found on city busses. I knew from the information booth that our ride would cost ¥150 but we had only larger bills and needed change. Despite our every effort to be quick as not to delay the passengers, it took us a minute to understand how the machine makes change. Quickly detecting our ignorance, the driver assisted by inserting the money into the correct slot, collecting the fare and handing back the change. Mom maintains he flashed us a look as to say "stupid tourist." If true, this was a rare example in a country filled with extremely polite and helpful people. After exiting the streetcar, we made our way from the small platform in the middle of the street to the

. Moving toward the streetcars, we find no customary fare machines and watch as scores of people get on without paying. The Route 6 streetcar departing at any moment, I decided we were smart enough to wing it and hopped aboard.

The older-looking streetcar is fairly crowded as it moves along the busy and modern city streets of downtown Hiroshima. Using the handle overhead to keep my balance standing, I try to inch gradually closer to the front of the car to try to figure out how exactly we pay the fare. After a few stops, I am finally able to see people paying at a device next to the driver similar to those found on city busses. I knew from the information booth that our ride would cost ¥150 but we had only larger bills and needed change. Despite our every effort to be quick as not to delay the passengers, it took us a minute to understand how the machine makes change. Quickly detecting our ignorance, the driver assisted by inserting the money into the correct slot, collecting the fare and handing back the change. Mom maintains he flashed us a look as to say "stupid tourist." If true, this was a rare example in a country filled with extremely polite and helpful people. After exiting the streetcar, we made our way from the small platform in the middle of the street to the  .

.

Also known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial and commonly called the A-Bomb Dome, the 1915 structure was one of the few not completely destroyed by the bomb. Originally the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall

Also known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial and commonly called the A-Bomb Dome, the 1915 structure was one of the few not completely destroyed by the bomb. Originally the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall  , the building was renamed to the Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall

, the building was renamed to the Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall  in 1921. During this time, the structure was used to display and sell prefectural products, house market research and small business consultation offices and serve as venue for art exhibitions, fairs and various cultural events. Later becoming the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall

in 1921. During this time, the structure was used to display and sell prefectural products, house market research and small business consultation offices and serve as venue for art exhibitions, fairs and various cultural events. Later becoming the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall  in 1933, the building would soon serve new purposes as promotional activities dwindled during the war. By April 1944, the building was home to the Interior Ministry Chugoku-Shikoku Public Works Office

in 1933, the building would soon serve new purposes as promotional activities dwindled during the war. By April 1944, the building was home to the Interior Ministry Chugoku-Shikoku Public Works Office  , the Hiroshima District Lumber Control Corporation

, the Hiroshima District Lumber Control Corporation  and other government offices.

and other government offices.

After the detonation of the

After the detonation of the  uranium bomb at 0815 JST, Monday, 06 August 1945, approximately 1,969 feet (600 metres) above and 525 feet (160 metres) to the southeast of the Dome, the building's occupants were instantly killed, the structure itself gutted by fire. Due to the direction of the blast and the physics at work, the walls and still-recognizable dome remained standing. In 1960, sixteen-year-old

uranium bomb at 0815 JST, Monday, 06 August 1945, approximately 1,969 feet (600 metres) above and 525 feet (160 metres) to the southeast of the Dome, the building's occupants were instantly killed, the structure itself gutted by fire. Due to the direction of the blast and the physics at work, the walls and still-recognizable dome remained standing. In 1960, sixteen-year-old  died of leukemia, exposed to the bomb 0.75 miles (1,250 metres) from the hypocentre at age one. After reading an excerpt from her diary which basically said, "I think only that ravaged Industrial Promotion Hall (A-bomb Dome) will be there to tell the world how fearsome atomic bombs are," the children of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, compelled to act on her behalf, started what became the Dome preservation movement. Their 1960 flyer containing Hiroko's quote helped the growing campaign and by 1966, the

died of leukemia, exposed to the bomb 0.75 miles (1,250 metres) from the hypocentre at age one. After reading an excerpt from her diary which basically said, "I think only that ravaged Industrial Promotion Hall (A-bomb Dome) will be there to tell the world how fearsome atomic bombs are," the children of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, compelled to act on her behalf, started what became the Dome preservation movement. Their 1960 flyer containing Hiroko's quote helped the growing campaign and by 1966, the  by the

by the  as a "stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind" and "the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons."

as a "stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind" and "the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons."

Walking south toward the Dome, the lush green and metropolitan surroundings are a strange contrast to the gutted structure, looking still as it did that Monday morning not so long ago. I silently walk around, photographing and taking it all in, as they say. Moving from the Dome and surrounding monuments, I come to the

Walking south toward the Dome, the lush green and metropolitan surroundings are a strange contrast to the gutted structure, looking still as it did that Monday morning not so long ago. I silently walk around, photographing and taking it all in, as they say. Moving from the Dome and surrounding monuments, I come to the  , completed 15 July 1967 to recognize the children forced by law to perform labor service who subsequently died in the bombing. Of the 8,400 middle school aged and older students in Hiroshima, 6,300 or 75% of them perished.

Crossing the

, completed 15 July 1967 to recognize the children forced by law to perform labor service who subsequently died in the bombing. Of the 8,400 middle school aged and older students in Hiroshima, 6,300 or 75% of them perished.

Crossing the  , we move into the main portion of

, we move into the main portion of  , encompassing 1.3 million square feet (122,100 square metres) of green parkland between the Honkawa

, encompassing 1.3 million square feet (122,100 square metres) of green parkland between the Honkawa  and Motoyasu

and Motoyasu  Rivers. After walking north to take pictures of the Dome from across the Motoyasu River, I moved south through the large collection of monuments and other remembrances starting with the

Rivers. After walking north to take pictures of the Dome from across the Motoyasu River, I moved south through the large collection of monuments and other remembrances starting with the  . Completed 28 October 1967, this unusually designed clock tower of 66 feet (20 metres) chimes daily at 0815 as a "prayer for perpetual peace and appeal to the peoples of the world that the wish be answered promptly."

. Completed 28 October 1967, this unusually designed clock tower of 66 feet (20 metres) chimes daily at 0815 as a "prayer for perpetual peace and appeal to the peoples of the world that the wish be answered promptly."

Next, I came to the

Next, I came to the  , dedicated 20 September 1964 "as a symbol of Hiroshima aspiration: let all nuclear arms and wars be gone and the nations live in true peace." Since all with the desire for peace are invited to chime the bell, I walked up, grabbed the hanging mallet and tolled. The muted but resonant sound was not very loud, but I was striking softly as instructed. In fact, my first attempt failed when the mallet had insufficient momentum to make contact with the bell's surface. I pulled back a little further on the second try and succeeded. While researching this article, I had occasion to watch many videos of Hiroshima visitors, all of whom had to try twice to ring the bell. I wonder if the mallet's rope is wound tight on purpose to help prevent excessive wear.

Continuing through the park, I next arrived at the

, dedicated 20 September 1964 "as a symbol of Hiroshima aspiration: let all nuclear arms and wars be gone and the nations live in true peace." Since all with the desire for peace are invited to chime the bell, I walked up, grabbed the hanging mallet and tolled. The muted but resonant sound was not very loud, but I was striking softly as instructed. In fact, my first attempt failed when the mallet had insufficient momentum to make contact with the bell's surface. I pulled back a little further on the second try and succeeded. While researching this article, I had occasion to watch many videos of Hiroshima visitors, all of whom had to try twice to ring the bell. I wonder if the mallet's rope is wound tight on purpose to help prevent excessive wear.

Continuing through the park, I next arrived at the  . Unveiled on 05 May 1958 as a monument to the children, the memorial itself was inspired by the death of twelve-year-old

. Unveiled on 05 May 1958 as a monument to the children, the memorial itself was inspired by the death of twelve-year-old  whose classmates began the call for such a monument. Paper cranes are continuously made and donated for display in the cases surrounding the three-legged monument pedestal, atop which stands the bronze figure of a girl holding a crane.

whose classmates began the call for such a monument. Paper cranes are continuously made and donated for display in the cases surrounding the three-legged monument pedestal, atop which stands the bronze figure of a girl holding a crane.

Backtracking a bit to catch the rest of the monuments on the northern side of the park, I reach the

Backtracking a bit to catch the rest of the monuments on the northern side of the park, I reach the  . After taking a few pictures, I find the sign and learn that this monument was the original site where deceased victims were gathered and cremated. The Hiroshima Memorial Service Association built the original cinerarium here in January 1946, which was later replaced by the City of Hiroshima in July 1955 by the current cinerarium and monument.

The next remembrance I came upon is the

. After taking a few pictures, I find the sign and learn that this monument was the original site where deceased victims were gathered and cremated. The Hiroshima Memorial Service Association built the original cinerarium here in January 1946, which was later replaced by the City of Hiroshima in July 1955 by the current cinerarium and monument.

The next remembrance I came upon is the  (06 August 1956), recognizing the former Nakajima

(06 August 1956), recognizing the former Nakajima  neighborhood, the present-day site of the Peace Park and preserved only in memory and detailed maps reconstructed by survivors. After the

neighborhood, the present-day site of the Peace Park and preserved only in memory and detailed maps reconstructed by survivors. After the  (10 April 1970), I moved toward the open, central part of the park and approached the

(10 April 1970), I moved toward the open, central part of the park and approached the  (Memorial Monument for Hiroshima, City of Peace)

(Memorial Monument for Hiroshima, City of Peace)  .

Built on 06 August 1952 with the desire to reconstruct Hiroshima as an enduring city of peace, the Cenotaph is constructed such that through it to the north can be seen the

.

Built on 06 August 1952 with the desire to reconstruct Hiroshima as an enduring city of peace, the Cenotaph is constructed such that through it to the north can be seen the  (01 August 1964) and Atomic Bomb Dome. The stone chest inside contains the official registry of all those who died as a result of the bombing, a figure of 221,893 as of 06 August 2001.

(01 August 1964) and Atomic Bomb Dome. The stone chest inside contains the official registry of all those who died as a result of the bombing, a figure of 221,893 as of 06 August 2001.

While observing the memorial, a man dressed in an all-white robe and

While observing the memorial, a man dressed in an all-white robe and  wooden sandals took position immediately in front of the Cenotaph and did what looked like

wooden sandals took position immediately in front of the Cenotaph and did what looked like  prayers due to their similarity to the rituals I observed a few days earlier at the

prayers due to their similarity to the rituals I observed a few days earlier at the  and

and  Shrines. After a moment, he assumed a military-style salute position and stood tall for a few minutes before gathering his belongings and leaving. We meanwhile explored the rest of the grounds nearby including the

Shrines. After a moment, he assumed a military-style salute position and stood tall for a few minutes before gathering his belongings and leaving. We meanwhile explored the rest of the grounds nearby including the  (August 1955) which we would later enter, the

(August 1955) which we would later enter, the  (05 September 1960) and the recently added

(05 September 1960) and the recently added  (30 July 2005).

Before heading back and visiting the museum, we frankly needed a break from the memorial and decided to see more of modern Hiroshima. Walking through the nearby neighborhoods, I found Hiroshima indistinguishable from any other Japanese city, crowded and bustling with life. No exception was the

(30 July 2005).

Before heading back and visiting the museum, we frankly needed a break from the memorial and decided to see more of modern Hiroshima. Walking through the nearby neighborhoods, I found Hiroshima indistinguishable from any other Japanese city, crowded and bustling with life. No exception was the  , which provided the opportunity to try some non-Japanese Japanese food.

, which provided the opportunity to try some non-Japanese Japanese food.

I had seen the signs for

I had seen the signs for  earlier on

earlier on  and elsewhere, but it was not until I saw the huge banner of a cheesy burger at the Hondori location did I understand what they sold. A Japanese burger, now how could I resist? I ordered the Cheese Straight Burger

and elsewhere, but it was not until I saw the huge banner of a cheesy burger at the Hondori location did I understand what they sold. A Japanese burger, now how could I resist? I ordered the Cheese Straight Burger  Set with French Fried Potato

Set with French Fried Potato  and a fountain drink. It was a tasty burger, too, similar but somehow different from a typical American fast food burger. And the fries, much like those I sampled the day before are distinctly different. I am not sure if it is the oil they are fried in or some other factor, but I really came to enjoy the crispier, slightly thicker-shelled and definitely less greasy version.

After lunch and some more walking around, it was time to return to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and tour the inside. The museum is comprehensive and contains many exhibits and artifacts, including a wristwatch stopped at 0815 by the force of the blast, a child's tricycle and metal helmet and a section of warped

and a fountain drink. It was a tasty burger, too, similar but somehow different from a typical American fast food burger. And the fries, much like those I sampled the day before are distinctly different. I am not sure if it is the oil they are fried in or some other factor, but I really came to enjoy the crispier, slightly thicker-shelled and definitely less greasy version.

After lunch and some more walking around, it was time to return to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and tour the inside. The museum is comprehensive and contains many exhibits and artifacts, including a wristwatch stopped at 0815 by the force of the blast, a child's tricycle and metal helmet and a section of warped  girder. While obviously discussing a serious and somber event, the material was presented in an informative and unbiased way I felt represented all sides and kept to the facts.

Some two hours later, we exited the museum and made our way to the

girder. While obviously discussing a serious and somber event, the material was presented in an informative and unbiased way I felt represented all sides and kept to the facts.

Some two hours later, we exited the museum and made our way to the  (2002), containing the

(2002), containing the  and resources like the victim name and photograph database and a vast library of memoirs and stories from the time and reflections thereafter.

It was now after 1700 JST, so we made a final pass through the park and stopped at the Aioi Bridge. I earlier learned in the museum that this unique T-shaped bridge was the designated target of the atomic bomb, though it missed by 984 feet (300 metres) and exploded over

and resources like the victim name and photograph database and a vast library of memoirs and stories from the time and reflections thereafter.

It was now after 1700 JST, so we made a final pass through the park and stopped at the Aioi Bridge. I earlier learned in the museum that this unique T-shaped bridge was the designated target of the atomic bomb, though it missed by 984 feet (300 metres) and exploded over  instead. This bridge, replacing the repaired original in 1983, stands as a kind of crow's nest from which you can look out in all directions and see the results of the past, the monuments to the lost and the progress forward already made in rebuilding Hiroshima into a vibrant, pleasant city.

instead. This bridge, replacing the repaired original in 1983, stands as a kind of crow's nest from which you can look out in all directions and see the results of the past, the monuments to the lost and the progress forward already made in rebuilding Hiroshima into a vibrant, pleasant city.

We walk to the same Hiroden streetcar stop we arrived at seven hours ago and get on the next Hiroshima Station-bound car that comes by, this time with a full understanding of how this unique transportation system works and exact change in hand. Waiting at Track 14 for the Tokaido Shinkansen Hikari 478 Rail Star to

We walk to the same Hiroden streetcar stop we arrived at seven hours ago and get on the next Hiroshima Station-bound car that comes by, this time with a full understanding of how this unique transportation system works and exact change in hand. Waiting at Track 14 for the Tokaido Shinkansen Hikari 478 Rail Star to  , the first leg in our long journey back to the apartment, we have been up for over fifteen hours. Although exhausted from the days of walking, I am surprised not to be as tired as expected.

, the first leg in our long journey back to the apartment, we have been up for over fifteen hours. Although exhausted from the days of walking, I am surprised not to be as tired as expected.

As the

As the  The especially helpful JR ticket clerk who booked our reserved Shinkansen tickets days earlier understood our requirements to leave and return on the same day. What this meant for us was catching the first and last trains of the day. The getting there portion of this worked flawlessly with time to spare, but included no train changes. The return trip, however, included one such change—giving us only six minutes to make our connection aboard the Hikari 434. We understood both trains would be near each other, but took no chances with the margin of error and were very prepared to depart the train when it pulled into Shin-Osaka Station.

We made the connection without issue and the rest of our trip back was uneventful, except for my sleepy mistaken impression we should exit the Odakyu train one station too early. We were close to home, but I was still very relieved to discover there was one last train that would take us from here to Odakyu-Sagamihara. Twenty-one hours and 210 pictures after starting this day, we were once again walking the darkened, mostly deserted streets of Sagamigaoka eagerly heading toward bed. Steven

The especially helpful JR ticket clerk who booked our reserved Shinkansen tickets days earlier understood our requirements to leave and return on the same day. What this meant for us was catching the first and last trains of the day. The getting there portion of this worked flawlessly with time to spare, but included no train changes. The return trip, however, included one such change—giving us only six minutes to make our connection aboard the Hikari 434. We understood both trains would be near each other, but took no chances with the margin of error and were very prepared to depart the train when it pulled into Shin-Osaka Station.

We made the connection without issue and the rest of our trip back was uneventful, except for my sleepy mistaken impression we should exit the Odakyu train one station too early. We were close to home, but I was still very relieved to discover there was one last train that would take us from here to Odakyu-Sagamihara. Twenty-one hours and 210 pictures after starting this day, we were once again walking the darkened, mostly deserted streets of Sagamigaoka eagerly heading toward bed. Steven  were anxious to hear about the day, but after a few quick highlights, I was on the floor mat drifting off to sleep, thinking about the hours past and days yet to come.

were anxious to hear about the day, but after a few quick highlights, I was on the floor mat drifting off to sleep, thinking about the hours past and days yet to come.