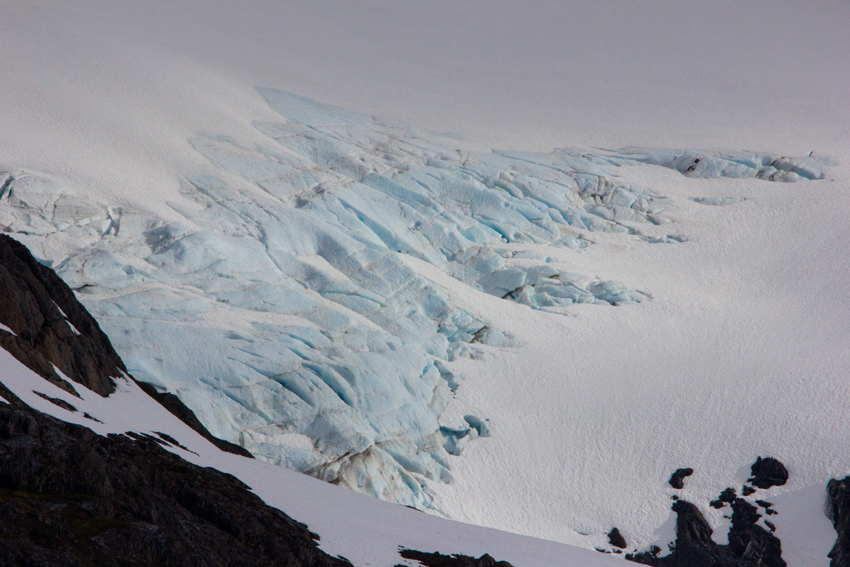

The blue ice of Middle Glacier in the Kenai Mountains visible from our Williwaw Campground site in the Chugach National Forest.

MP 4.1 Portage Glacier Road, Portage Valley, Alaska: 19 June 2017

part of the Alaska 2017: Portage Valley album

To serve as base camp during our time visiting Seward, Whittier and Prince William Sound, Mom selected an absolutely perfect campground nestled within Portage Valley in the Chugach National Forest. A facility of the United States Forest Service, Williwaw Campground is located about five miles west of Whittier and features nature trails, wildlife and spectacular views.

Driving to the campground from Seward Highway on Portage Glacier Road in a glaciated valley, one is surrounded by lush forests and looming, snow-covered mountains. It is a serene environment, even on an overcast and drizzly day. Near the start, there is a roadside sign for Portage Valley and the Chugach National Forest, a woodland spanning 5,361,803 acres and "comprised of arid tundra wilderness, jagged mountains, deep fjords and glacier-fed rivers that surround the Prince William Sound."

As in many areas throughout Alaska, Portage Glacier Road is lined with snow marker poles in sections, including just outside the Williwaw Campground. These safety devices allow wintertime drivers to see the edges of the roadway when the surface is covered with snow and ice.

Upon our initial arrival on Monday, 19 June 2017 at Williwaw Site 6, a large pull-through campsite surrounded by forest, my attention was immediately drawn to the glacier hanging in the nearby Kenai Mountains. Breathing in the crisp, cool air and enjoying the relative silence of this wilderness area, I walked around the spacious site and tried to capture through photographs the stunning blue ice of Middle Glacier. There are a number of nearby glaciers, including Explorer Glacier to the west and Byron Glacier to the east, but I was ecstatic seeing one right from our campsite.

After taking several photos, I switched to Mom's Tamron SP 150–600mm lens — her big Christmas present from 2016 — and took additional closeup shots of Middle Glacier, including the one atop this article. I was amazed by the beauty of blue ice.

The campsites at Williwaw are nicely spaced compared to many other campgrounds. There are no connections for electricity, water or sewers, but water pumps and vault toilets are placed around the campground for tent campers.

Wildlife typical to Alaska are known to frequent the area, yet despite the numerous bear warning signs around, our only animal encounter was with a moose. It happened to be in our campsite one morning as we opened the camper door, but quickly ran off into the woods leaving some tracks behind.

Two nature trails are accessible from the campground, one of which we briefly explored before departing the area on Thursday, 22 June 2017. Following a small trail just east of our campsite leads to a parking lot accessible from Portage Glacier Road. This lot is for the Williwaw Fish Viewing Platform, where a boardwalk allows visitors to watch spawning sockeye, chum and coho salmon in the stream from their arrival in late summer through early autumn.

Beginning next to the platform, the Williwaw Nature Trail (1.25 miles) follows the Williwaw Creek under Portage Glacier Road over to an area with four ponds. After winding around the ponds, the trail crosses the road and heads south to an intersection with the Trail of Blue Ice (5 miles), running between the Moose Flats Day Use Area and Portage Lake.

Back on Monday, not long after our arrival and my glacial photo shoot, we built a campfire. It was chilly that day (high 58° F, low 32° F), so we sat closely around the fire for its warmth. I also enjoyed a few bottles of Coldfoot Pilsner Lager by Silver Gulch Brewing and Bottling Company based in Fox, Alaska.

From my seat at the fire, I need only look up in between the trees to see Middle Glacier. Except for a neighboring camper who bafflingly ran a generator for a while, Williwaw Campground was quiet, peaceful and absolutely wonderful.