A Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) stops and looks at us from the brush alongside the Dalton Highway (AK 11) shortly after crossing the road southwest of Sukakpak Mountain.

MP 202.4 James W. Dalton Highway, Yukon-Koyukuk, Alaska: 24 June 2017

part of the Alaska 2017: Wiseman to Prudhoe Bay album

It all happened so quickly, taking about one minute total.

We had left the excellently quaint village of Wiseman about forty-five minutes earlier to continue our journey to Prudhoe Bay northbound on the James W. Dalton Highway. This section of the road was paved and in relatively good condition, but I still kept my speed down because we were enjoying the drive, scenery and were always watching for animals. Shortly after passing Milepost 202 and coming over a small hill, an animal approached the roadway on the right side and then swiftly jogged across.

I immediately started slowing down and raised my camera to fire off several frames from the hip, looking not at my camera but focusing on driving safely. Mom was the one to guess what we had come across and the notion was rather exciting. I brought the car to a stop where the animal had left the roadway and entered the brush. Sure enough, darting away from us was a Canada lynx.

As they are known to be nocturnal, elusive and an avoider of human contact, it was awesome to see a lynx in the wilderness, let alone just before noon. Despite the name, Canada lynx inhabit forests in Canada and Alaska with additional populations in the lower forty-eight — where it is considered a threatened species — in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming. Twice the size of a domestic cat, the Canada lynx sports hair tufts atop its ears, long lower cheek ruffles and a short, black-tipped tail.

Fortunately, the lynx stopped not too far away to check us out for a moment, staring with typical feline intensity.

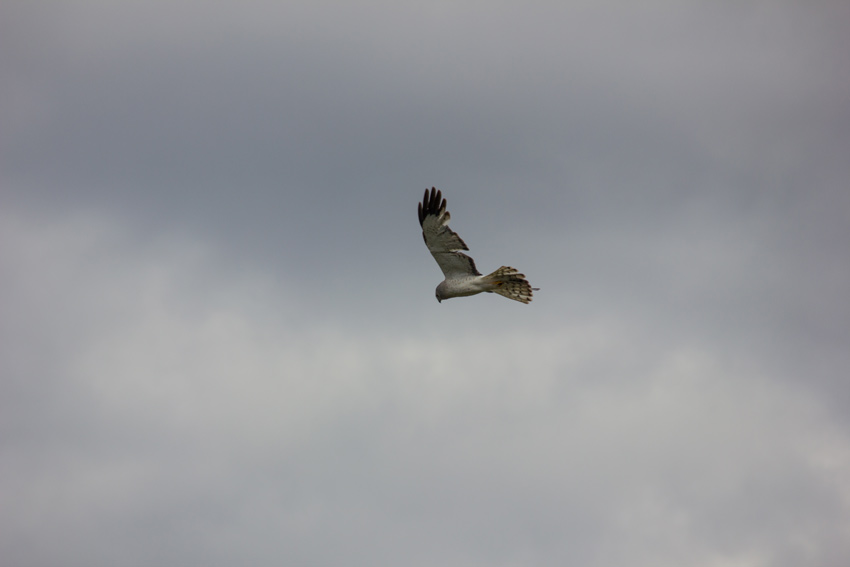

Just as the lynx decided to retreat into the thicker forest and out of visual range, my attention was drawn to a sound from above. Circling overhead and screeching loudly was a northern harrier, a hawk that breeds in Alaska and Northern Canada.

Although it seemed quite upset by the big cat's presence, the northern harrier probably did not have much to worry about. Canada lynx in these northern regions feed almost exclusively on snowshoe hare, large rabbits that are white in the winter and then brown in the summer. Cyclical patterns in hare populations affect the lynx as well; as the number of hares increase and decrease, so does the number of lynx. From what we saw, the local hare population was on the rise.

Even though we could no longer see the lynx, we watched the northern harrier continue to circle and squawk in the sky, each circle moving further from the road as the cat continued away. We soon left as well, but were especially pleased with our good fortune. Two days later on the drive back to Fairbanks, we again stopped at the Arctic Interagency Visitor Center in Coldfoot and told the rangers there of our various animal sightings in the area and up in Prudhoe Bay.

I saw so many kinds of animals during my Alaska adventure, several of them rather close, but the Canada lynx was certainly a rarer find and something I am fortunate to have seen.